Researching “Old” War, Experiencing “New” War

Oksana Dudko, Petro Jacyk Postdoctoral Fellow in Ukrainian Studies, details new reality in Ukraine

By Oksana Dudko

In Summer 2021, I was delighted to receive a Jacyk Postdoctoral Fellowship in Ukrainian Studies at St Thomas More College, especially because the affiliated Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage is the perfect place to pursue my research about Ukrainian history. My dissertation research examines how continued violence after the First World War and the Ukrainian and Russian revolutions shaped the identities of Galician Ukrainian soldiers. When I began the fellowship, I was excited to work on turning my dissertation into a book project. What I didn’t know is that I would be finishing this research about war and violence while simultaneously living through a full-fledged war in Ukraine, my home country.

My academic year in Saskatoon began with beautiful summer walks and bike rides with my family along the Meewasin Valley. After living through a strict COVID-19 lockdown in Toronto, it was a great way to start the academic year. I was also thrilled about the opportunity to teach two courses: the Soviet Union and Modern Ukraine and Russian–Ukrainian Conflict. In the latter course, I taught students about the complex Ukrainian–Russian relationship that has spanned centuries. In particular, we explored the historical preconditions of the Russian proxy war in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea. We also critically evaluated how the medieval and premodern history of Ukraine has been weaponized in Putin’s historical imagination and Russian propaganda.

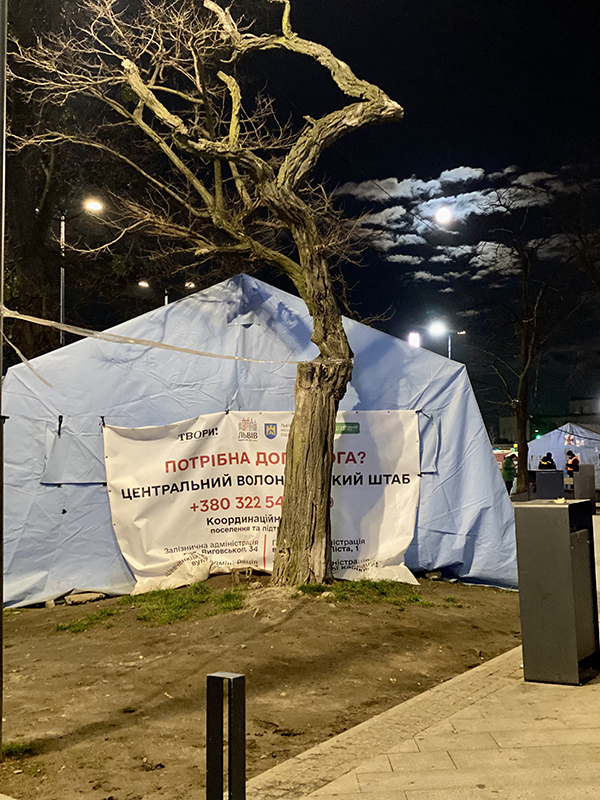

However, my teaching and research at St Thomas More College were interrupted by the full-fledged Russian invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022. When the war started, I immediately rushed to Ukraine to provide support and evacuate two vulnerable family members. When I transited through Warsaw, I was impressed by the enormous support for Ukraine and volunteer initiatives. I also reunited with distressed friends who had fled the country immediately to keep their kids safe. At the time, Kharkiv was being heavily shelled, so I volunteered to collect medical supplies for local residents with my friend Roza Sarkisian, a theatre director whose family was trapped in the city. After I arrived in Lviv, Roza and I continued to help Kharkiv residents obtain essential medical supplies. I also continued teaching the Ukrainian history course online, incorporating my first-hand experience of the war into the classes.

In Lviv, several civilians have been killed or injured and local infrastructure has been destroyed by Russian missile strikes. Hearing air raid sirens and sheltering in basements has also become part of everyday life. However, because Lviv is far from the regions hit by direct fighting, it has become a hub for people fleeing from different parts of the country. As a researcher and interviewer, I’ve joined an international initiative to gather testimonies from such people about their war experiences. When I return to Saskatoon, I hope to begin a new research project to gather and examine the testimonies of Ukrainians who were forced to flee the war and are now starting a new life in Saskatchewan.