STM's Kordan helps preserve the history of local internment camp

Eaton Internment Camp Permanent Exhibit was officially opened at the Saskatchewan Railway Museum.

By Paul Sinkewicz

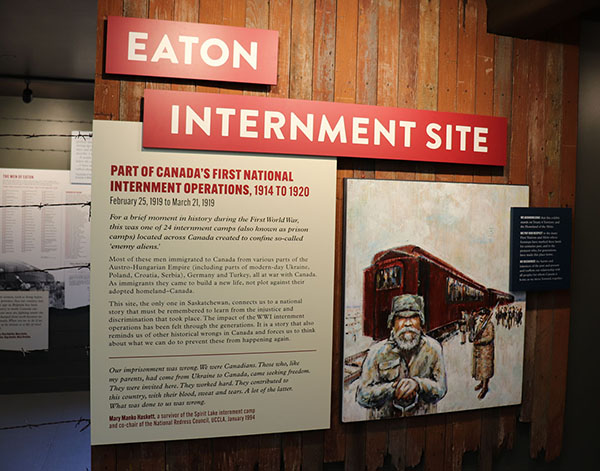

The retired professor of political studies at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and the founding director of the Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage (PCUH) at St. Thomas More College (STM) has been researching and writing about Canada’s ‘enemy aliens’ for more than 30 years. His academic work has contributed to healing a wound in the Ukrainian-Canadian community by shining a light on past injustices, and by bringing a new museum exhibit to life that will continue that work into the future. The Eaton Internment Camp Permanent Exhibit was officially opened on June 4 at the Saskatchewan Railway Museum.

Kordan said its lessons will teach generations to come about the dangers of fear borne of conflict and mixed with racial or ethnic animus.

For more than 8,500 men, women and children during the First World War, Canada was a land of broken promises. They had emigrated from Europe in the hopes of building a life of prosperity in the burgeoning democracy but would find themselves helpless pawns in the politics of the time.

After the outbreak of hostilities, the Canadian government passed the War Measures Act, giving itself sweeping powers to arrest and detain Canadian immigrants from Germany or Austria-Hungary. Most of the detainees were of German or Ukrainian heritage, and had committed no crimes, but did have the misfortune of being unemployed or homeless. They were swept up by authorities and became prisoners of the state, housed in internment camps across the country. Most were single men, but some had families that voluntarily joined them behind barbed wire.

Another 80,000-plus were forced to register as ‘enemy aliens’ with the government and produce documentation when it was demanded as part of a surveillance system.

“My interest in the issue stems from two basic questions: how did this happen and why has it disappeared from public memory?” said Kordan. “In attempting to address these questions, I embarked on a long journey of discovery, coming to know Canada in unexpected ways. It was a Canada that I neither knew nor recognized. It underscored for me the importance of making the experience more well-known—to use my skills to integrate the story into the discourse about the nature of Canada, its promise but also pitfalls. The permanent display at the Saskatchewan Railway Museum, which I was privileged to be involved with, helps make this possible. My hope is that the exhibit will become part of the local but also larger conversation about rights and human dignity.”

In June 2022, a grand opening ceremony took place just outside Saskatoon ensuring the memory of that period of fear and discrimination in Canada’s history would not be forgotten by future generations.

The Eaton Internment Camp only played a brief role in the story of Canada’s internment operations. On Feb. 25, 1919, 65 prisoners were relocated from the Munson Internment Camp in Alberta to the railway siding at Eaton. But a lack of confidence in the military guard prompted authorities to abandon the location for more secure facilities, and just 24 days after it was initially established, the internees were transported to a military installation in Nova Scotia, where they would await their eventual deportation. The Eaton camp was dismantled shortly after their removal.

Cal Sexsmith, president of the Saskatchewan Railway Museum, said the project was nearly 20 years in the making. It started with Kordan visiting the site to confirm it as the location of the Eaton camp. What resulted from that visit was a monument erected in 2004 and the start of discussion about a permanent interpretive exhibit. In 2022, all the work came to fruition thanks to volunteers from the Saskatchewan Railroad Historical Association, who constructed the exhibit with the help of a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

Kordan said the question of whether Canada is at risk of ever making such a mistake again is dependent upon honouring history and teaching following generations about the past—the very purpose of the new exhibit. He said those who made political decisions around internment at the time understood the moral choice they were confronted with and chose to ignore it.

“Fundamentally, politics is about moral choices,” said Kordan, who retired from USask in 2021. “Can this happen again? Confronted by political challenges, bad decisions can occur, and the wrong moral choices can be made. So, yes, from this perspective, such tragedies can happen again. However, it is less likely to occur if we are taught and learn about the past. It starts with the children, sensitizing them to the issue of rights, making them aware of the importance of protecting the vulnerable and less fortunate. As a teaching tool, where young people will visit and learn about what happened on this site, the permanent display will look to make this possible.”

Providing awareness and standing up against injustices for the peoples of Ukraine is nothing new for Kordan. As former head of STM’s Department of Political Studies, Kordan specialized in nationalism, ethnic conflict and state minority relations; Canadian foreign policy; and contemporary Ukraine. His passion in this area led to his role in founding the PCUH at STM in 1995. Kordan remains invested in the promotion and support of PCUH’s mission to advance study of various aspects of Ukrainian heritage, culture, and life, while supporting the long and pioneering tradition of Ukrainian Studies at USask—home province for a large Ukrainian population—by providing context for the university’s Ukrainian Studies Certificate program, while also guiding the work of graduate students with an interest in Ukrainian studies.

The Eaton Internment Camp Permanent Exhibit was created through a partnership involving the PCUH, the Ukrainian Canadian Congress–Saskatchewan Provincial Council, the Saskatchewan German Council, and the Saskatchewan Railway Museum. The museum is located southwest of Saskatoon, at the junction of Highway 60 and the Canadian National Railway line.

A recording of the June 4, 2022 ceremony is available HERE.

Dr. Bohdan Kordan, is an emeritus professor at St. Thomas More College (STM), retiring in 2021. He is a former head of the Political Studies Department at STM and taught in the College of Arts and Sciences at USask, specializing in Nationalism, Conflict, State Minority Relations; Canadian Foreign Policy; Historical Cartography of Eastern Europe; and Contemporary Ukraine. Kordan was the founding director of the Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage (PCUH) at St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan in 1995.

His past publications on the subject of internment include:

Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Internment in Canada During the Great War, 2002

No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience, 2016

In the Shadow of the Rockies, 1991

He has also appeared in a 2020 Shaw vignette about the Eaton Camp available on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbaggN2yOts

Remarks of Dr. Bohdan Kordan, Professor Emeritus, Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan at the official opening of the permanent Eaton Internment display, Saskatchewan Railway Museum, 4 June 2022, 10:00 am.

On a February day some 103 years ago, something unusual happened on this very site – Eaton as it was then known. A train pulled up to the siding and off-loaded its human cargo. It was a small group – sixty-five men in total – who had been relocated from Munson, Alberta, a railway junction down the line where, earlier, they had escaped the harrowing experience of the 1918 Spanish Influenza and a train wreck that nearly claimed their lives. Having arrived at this new destination and under the watchful eye of a small detachment of Canadian soldiers, they surveyed their new surroundings. Looking out at the open prairie, they would have despaired. The endless horizon was a metaphor for their sense of loss and abandonment. Confined in railway cars and put to work under armed guard repairing track, they were mystified as to why they were being subjected to such cruel treatment. What had they done to deserve this?

Invited by the promise of opportunity, they had immigrated earlier to Canada. For most Canadians, these new arrivals were unfamiliar, strangers yet neighbours, they spoke a language and engaged in customs and habits not easily understood but whose labour was needed. Originating from lands now at war with Britain and the Empire, they would be designated aliens of enemy origin as fear and suspicion surfaced with war’s onset. The allegiances of such people, it was felt, lay with their ancestral lands, not Canada. As a result, under emergency legislation – the War Measures Act – the government of Canada issued orders enabling it to monitor and, if needed, intern as prisoners of war those identified as enemy aliens.

The emergency powers granted the government under the Act also enabled it to deal with growing unemployment among the enemy alien population, the result of a contracting economy and a hostile public that saw foreigners as competitors and rivals. The government would resort to internment to address the problem. With nowhere to go and no prospect of employment, some 8,579 enemy aliens, mostly of Ukrainian origin, were interned as war prisoners. Of those detained, the majority were destitute and unemployed. They were apprehended across Canada in various cities -- Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, Victoria, and Saskatoon – as well as towns – Lethbridge, Brandon, Nanaimo, and Moose Jaw – and villages and hamlets, including Lamont, Ladysmith, Fernie, Melville, Willkie, and Dauphin. An additional 80,000 were required to register, always carry identification papers, and report weekly to local magistrates or other officials, all of whom would pass judgment over their lives and freedom.

The arrests prompted the government to establish internment camps, primarily located in the Canadian hinterland of the Rocky Mountains, the northlands of Ontario and Quebec, and the BC interior. In total, twenty-four facilities were created. As prisoners of war, the internees would be subject to military discipline, and at the point of a bayonet, forced to work clearing land and constructing roads under arduous and difficult conditions. In Banff, Jasper, Revelstoke, and Yoho National Parks and at Morrisey, Kapuskasing and Spirit Lake, they cleared bush and built roads. At Valcartier and Petawawa they expanded the military training grounds and artillery ranges. Near Truro, Dartmouth and Moncton, and later Munson, Alberta and Eaton, Saskatchewan, they repaired and laid new track. Throughout the ordeal, disobedience and defiance were met with corporal and other forms of punishment. Scores looked to escape. A few were shot in the attempt. Others fell into a deep melancholia and, succumbing to mental anguish, took their own lives. Most, however, chose to remain silent. Believing this was all a mistake, they waited in anxious disbelief for the war to end.

The experience of WWI internment represents a grim yet largely unknown episode in Canada’s history of participation in the Great War. It would involve the unjust treatment of immigrants who called Canada their home. As we reflect on this historical wrong, we are reminded about the importance of rights and freedoms, especially when the din of war overwhelms reason, and the hearts of men are hardened. To them – to the tens of thousands who were forced to register and report because they were designated enemies of Canada and to the thousands interned as war prisoners for no other reason than because of who they were and where they came from – we have a duty to remember.

As we open this permanent exhibit at the Saskatchewan Railway Museum, we reflect on the trials of those who were brought here. We also remember the many thousands interned elsewhere, who would return to their families and homes, picking up the pieces of their broken lives, pondering over the experience and the failed promise of Canada. We remember their pain, suffering, and misery. The goal, however, is not to engage in recrimination or blame, nor stoke the fires of resentment. Rather through this exhibit we invoke the memory of these past events as an act of reconciliation, declaring openly that a wrong was committed and an injustice had taken place here. Today, we launch this permanent exhibit as an act of political faith, stating unequivocally that history shall not be repeated and to alert future generations of the responsibility and obligation that we owe each other – to be tolerant, understanding, and caring.

But we also open this museum display today as the culmination of a partnership between various communities – Ukrainian and German – as well as organizations – the Saskatchewan Railway Museum and the Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage at St. Thomas More College – who have come together to create this legacy, so that future generations may remember the importance of preserving rights and liberties. Most importantly, however, through your attendance here and participation in this ceremony you demonstrate your commitment to this enterprise. In doing so, you are reaching into the future, standing in solidarity with your children and your children’s children; knowing that when they come here to learn and reflect, they will grow to be more aware citizens, making Canada truly ‘strong and free.’